Recently a young woman got in touch to ask if a women’s circle that I was running would be open to her non-binary friend. Instinctively I knew my answer was No, but why? I got round it with logic – I’d advertised an event for women; someone who is calling themselves non-binary is not a woman; ergo, it is not for them. But I wondered if I had done right. What about inclusivity? And what would I have said about a transgender woman? I did a lot of thinking.

The first thing I came up with is that circles are for everyone. Recently I have been sitting in circle with primary school children as part of a peace education programme, and I regularly facilitate circles for people to share responses to the climate emergency in our area. Circles are a wonderful way to bring people together in a safe and respectful way, and I would be very happy to to be in one that included non-binary or transgender people. Indeed I probably already have.

But a circle will usually exclude people as well as including them. The circle for the primary school children is closed to secondary school pupils. The climate emergency circle is open to everyone in principle, but if someone came along to argue that in fact there is no climate emergency, they would have to leave. These are not arbitrary rules based on hatred or phobia, but essential conditions that serve the principle on which the circle is based. It isn’t kind to invite people to a group where they won’t fit. (For a clear account of how it can be kind to exclude people, see Priya Parker’s book The Art of Gathering).

The question therefore is, what is the principle that underlies a women’s circle? There are many possible answers, and some will be more inclusive of non-binary and transgender women than others. You might for instance want to bring together people who have an interest in women’s issues generally, and naturally see transgender women as part of that conversation. Or, given that we live in a society where men’s voices are so prominent, the guiding principle could be one of privileging perspectives that are less often heard. Again the entry criteria could be broad, and some people have made inclusiveness their priority.

But there are other reasons for wanting to be in women’s circle. For me, it is to do with exploring what it means to have been born into a female body, and all the conditioning that goes with that. It is about seeing how I have picked up a particular view of what is possible for me to do, directly or indirectly as a result of that body, and questioning that. It is also about seeing how I have been trained to find my self-worth in caring for others, and learning a more intelligent form of giving that includes my own needs. It is learning to balance love with power.

For that, you need psychological safety. It is difficult to go to those tender and often shameful places in the company of people who may not understand, because they have not had that experience. When you are trying to be honest about your habits of self-effacement and people-pleasing, you do not want to be sitting next to the local equivalent of Caitlyn Jenner, who won Olympic gold medals as a man before posing glamorously on the cover of Vanity Fair as a woman.

The need for safety becomes even stronger, of course, when one of your reasons for seeking out a women-only space is that you have been raped or bullied by men. But it goes beyond that. Bonding over shared victimhood is something women have often done, and it’s a necessary step for many, but it only takes us so far. A women’s circle is also a place to connect with other women through affirmation and strength, daring to create a new society run on more feminine lines – less competitive and hierarchical, more cooperative and nurturing.

This brings us to the question of sex and gender. Sex is a biological term, while gender is about our cultural roles. A woman’s body is shaped for bringing new life into the world and for nurturing it, and that symbolism is ever present, even if we do not literally give birth. Linked to that, we tend to fall into the role of caring for children, old people and our communities generally. That is an example of a gender role.

This is not inevitable of course, and there is now a growing movement which says that sex is irrelevant, and what really counts is our ‘gender identity’. On this basis someone born a man or a woman, can announce themselves to be of the opposite gender to that, or neither, and have an absolute right to be seen as such. Thus ‘trans women are women’ and if we do not include them in a women’s circle, then we are being transphobic.

On the face of it, to cut gender loose from sex might seem a progressive move, producing freedom for all. Feminist thinking has fought hard against the tight link between sex and gender roles, which has been used to keep women in their place and deny them a political voice. The growing visibility of transgender and non-binary people takes us further in that direction and made us all question some received thinking, which is something to be grateful for.

By the same token, though, such a great change should not go unquestioned. Do we really want to ignore biological sex altogether? I can see at least two grounds for concern. One is that our bodies are not just our individual property. They have their own mysterious intelligence, holding memories of the younger selves we once were and connecting us with our parents, our ancestors and the natural world of which they are made. We might well change them, surgically or otherwise, but I think we ought not to discount them altogether. It is our bodies that have determined the upbringings we have had and so shaped our lives.

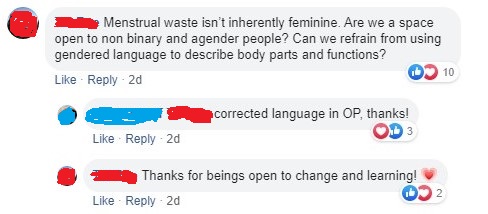

The other is that if we blur the difference between the sexes, then we all know which one is going to lose out. It is female athletes who take second place to transgender women, women’s spaces that are open to invasion by unscrupulous men, and women’s culture that is erased; men can carry on much as before. The effects on language are bizarre: a recent Facebook complaint to the effect that menstruation ‘isn’t inherently feminine’ was met with an apology and a flurry of likes.

The other is that if we blur the difference between the sexes, then we all know which one is going to lose out. It is female athletes who take second place to transgender women, women’s spaces that are open to invasion by unscrupulous men, and women’s culture that is erased; men can carry on much as before. The effects on language are bizarre: a recent Facebook complaint to the effect that menstruation ‘isn’t inherently feminine’ was met with an apology and a flurry of likes.

We need to be able to talk about all this, which is another reason for old-style women’s circles. This isn’t about whipping up hate or bigotry. On the contrary, it is about gaining a deeper understanding of sex and gender, and coming up with a kind and fair response to the challenge – which is what it is – of modern gender politics.

This month a campaign within the Labour Party asserted that “there is no material conflict between trans rights and women’s rights“and “all trans women are subject to misogyny and patriarchal oppression”. Many women’s groups would disagree with that, including Women’s Place UK, which the campaign accordingly terms a “trans-exclusionist hate group”. The argument is bitter and complex. Perhaps surprisingly, even some transgender people are ready to defend the priority of sex over gender.

The argument matters because it goes to the heart of what it is to be a woman. We must be allowed to have our own spaces, before we can decide who is to be invited into them.